Safarjaliyya (from safarjal, Arabic for ‘quince’) is found in multiple period sources, including the two I consulted: A Baghdad Cookery Book and An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the Thirteenth Century. The two recipes agree on the fundamentals (meat, vinegar, coriander seed, quinces, and saffron) but differ in execution. Andalusian has the meat cooked in oil, additional flavour from pepper, caraway and onion, and a thickener of eggs; Baghdad cooks the meat in “tail fat” and adds salt, cinnamon, mastic, minced meat ‘with the spices for meatballs’, rose water, and almond milk as a thickener.

I had started out looking for a medieval quince recipe for Okynfirth’s Autumn Revel because I’d seen a few weeks earlier that my mother in law’s quince bush was loaded with fruit. However, by the time the day came the quinces had become overripe and were no good even for cooking. Undeterred, I scoured the local big supermarket and came away with a jar of quince jelly. I was also unable to get mastic before the event, and knew one of the revel attendees has a nut allergy, so I ended up combining the two recipes to create my own version.

Measurements are homely because I was cooking at a village hall and forgot my measuring spoons; I would recommend tasting at every point!

Ingredients

- 300g diced casserole lamb

- 500g diced casserole beef

- One large brown onion, diced small

- Large blob of butter

- Large pinch of grains of paradise

- Dessertspoonful of caraway seeds

- About two teaspoonfuls of cinnamon

- About a teaspoonful of ground coriander seeds

- A pinch of salt

- 250g jar quince jelly

- Perhaps 3 dessertspoonfuls of rose water

- 3 eggs, beaten

- Large pinch of saffron

- Water

Method

- In a large stock pot, melt the butter and use it to brown the diced onion over a medium heat.

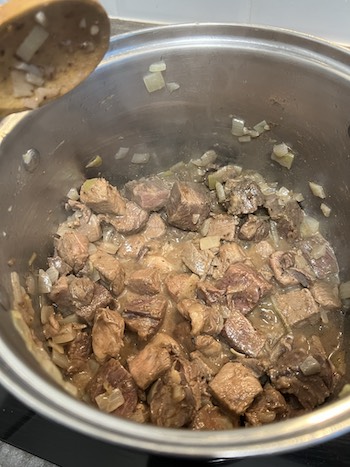

- Add the lamb and beef and brown the outsides.

- In a mortar and pestle, grind the grains of paradise and caraway seeds with the salt

- Add the cinnamon and ground coriander seeds to the other spices.

- Once browned, turn the meat and onions down to a low heat and sprinkle the spices over them.

- Add enough water to the pot to cover the meat and onions well.

- Spoon in the whole jar of quince jelly and stir well until the jelly has dissolved into the water.

- Bring the water to a boil then turn down to a low simmer. Leave simmering lightly, uncovered, for around 2 hours.

- Around the 2 hour mark, taste the broth and season if needed.

- Add the rose water.

- In a separate large mixing bowl, beat the eggs thoroughly.

- Continue to beat or whisk the eggs constantly whilst adding a dessertspoonful of the broth at a time. Go slowly or the eggs will curdle! Continue until the egg and broth mixture has reached the same temperature as the broth.

- Stirring the pot constantly, add the egg and broth mixture very slowly. This should thicken the sauce without turning it into scrambled eggs.

- Add the saffron and stir thoroughly. If you can, add a lot more saffron than I did.

- The dish is now ready but can be kept on a low heat for a little while longer if you’re not quite ready to serve.

This was a meaty, rich, sweet-sour tasting stew, which went excellently over rice or sopped up with thick slices of buttered bread. It didn’t have the most attractive colour – hence the suggestion of adding a lot more saffron – but the taste more than made up for it!

References

An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the Thirteenth Century, a translation by Charles Perry of the Arabic edition of Ambrosio Huici Miranda with the assistance of an English translation by Elise Fleming, Stephen Bloch, Habib ibn al-Andalusi and Janet Hinson of the Spanish translation by Ambrosio Huici Miranda, published in full in the 5th edition of volume II of the cookbook collection. Accessed via http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/cariadoc/recipes_introduction.html

A Baghdad Cookery Book, a translation by Charles Perry of The Book of Dishes (Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh) by Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan b. Muḥammad b. al-Karīm, the Scribe of Baghdad. Prospect Books, 2005.