Thoughts from an exhibition at The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford

Chaucer was inescapable where I grew up - I went to school in Canterbury, and lived for most of my life in Boughton, a village mentioned as one of the final stops for the weary pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales. Perhaps because of this, in some ongoing fit of teenage contrariness, I have never read or shown any interest in Chaucer’s work - Paul Bettany’s performance in A Knight’s Tale aside. So when I say that this exhibition actually got me more interested in and excited about Chaucer than I have ever been, that is no mean feat.

“Chaucer Here and Now” is a free exhibition on display at the Weston Library in Oxford until April 28th, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. You can just walk in, or there are also free gallery tours between 2pm and 2:45 on Wednesdays and Saturdays. On the penultimate day of the exhibition (Saturday 27th April), there is also a “Creating Chaucer” event where talks about the exhibition will be held, and you can also create your own traveller’s tale or participate in other activities.

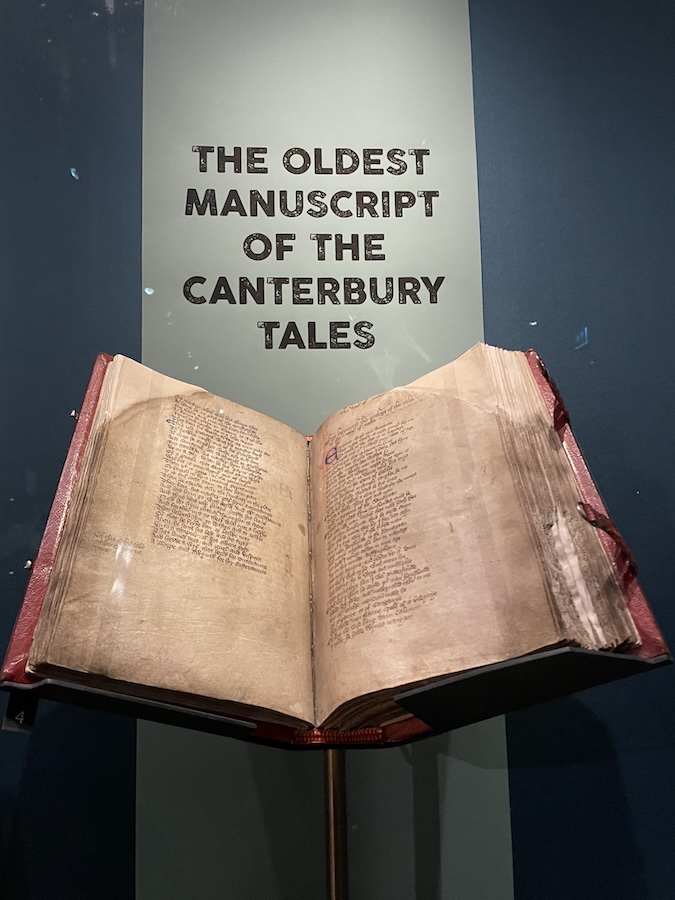

The exhibition opens with the earliest known manuscript of Chaucer’s work, the Hengwrt Chaucer, on loan from the National Library of Wales. Copied by one of Chaucer’s London-based associates, it was made around the time of his death. It has been fully digitised and is available online on the National Library of Wales’ website: https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/manuscripts/the-middle-ages/the-hengwrt-chaucer.

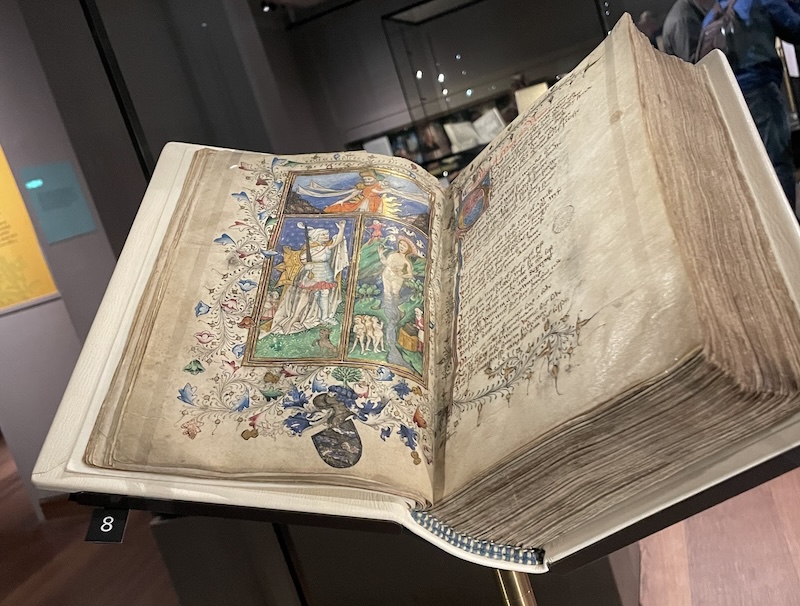

Also on display in this section are other gorgeous works, such as a fifteenth century miscellany of poetry (MS. Fairfax 16, digitised in full here: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ee2d3617-5696-4ec8-9e4d-a99d0c485019/), depicting a gorgeous illumination, in which Jupiter is suspended above Mars on the left and Venus on the right (see below); a manuscript of Troilus and Criseyde open to the frontispiece in which Chaucer is illustrated reading the poem to the court of King Richard II of England; and William Caxton’s first and second printed editions of the Tales.

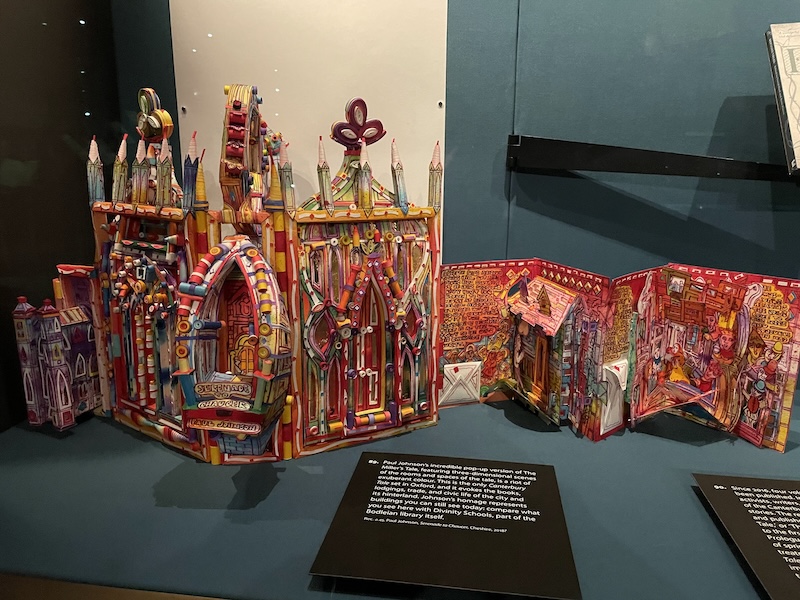

Where this exhibition really shines, however, are the other objects on display. With dedicated sections to translations into other languages, rewritings by other authors, and visual adaptations, the majority of the gallery examines how Chaucer’s work has been interpreted and reinvented over the centuries, and his relevance today. Regrettably, I didn’t get any photos of The Kelmscott Chaucer, printed by William Morris’ Kelmscott Press in 1896, or any of the other eighteenth or nineteenth century printings (which often censored the ruder parts, as did the children’s editions on display). The exhibition dives into how Chaucer’s work was co-opted by the British Empire for cultural colonialism and moral education, and contrasts it with contemporary responses, particularly those by women and people of colour. My favourite of these was Paul Johnson’s Serenade to Chaucer, a reimagining of The Miller’s Tale as a colourful papercraft pop-up book, with three-dimensional renderings of the spaces and scenes within the tale.

I loved this exhibition so much, and would recommend it to anyone, partially because what it is doing and the story it is telling aligns so closely with the goals and mindset of the SCA. That is to say, it celebrates creative engagement with history and historic literature (including the ugly parts), from how medieval scribes and editors finished off tales or added their own commentary to the work, through to how it continues to inspire people today.