Thoughts from an exhibition at Magdalene College, Cambridge.

In conjunction with the Magdalene College Triennial Festival 2024, Magdalene College Cambridge put on a display this year of medieval manuscripts from the college’s Pepys and Old Libraries, revealing ‘medieval perspectives on the physical world, on other worlds, and on the creative potential of image and word with the natural world, with music and with science’ (https://www.magd.cam.ac.uk/events/the-perspective-of-the-medieval-scribe).

I was only able to access half of the exhibition, because the other half was up stairs without a lift, but I am delighted to share what I can with you. What was on display in the Robert Cripps Gallery was at least cohesive, so it didn’t feel like I was only experiencing half an exhibit.

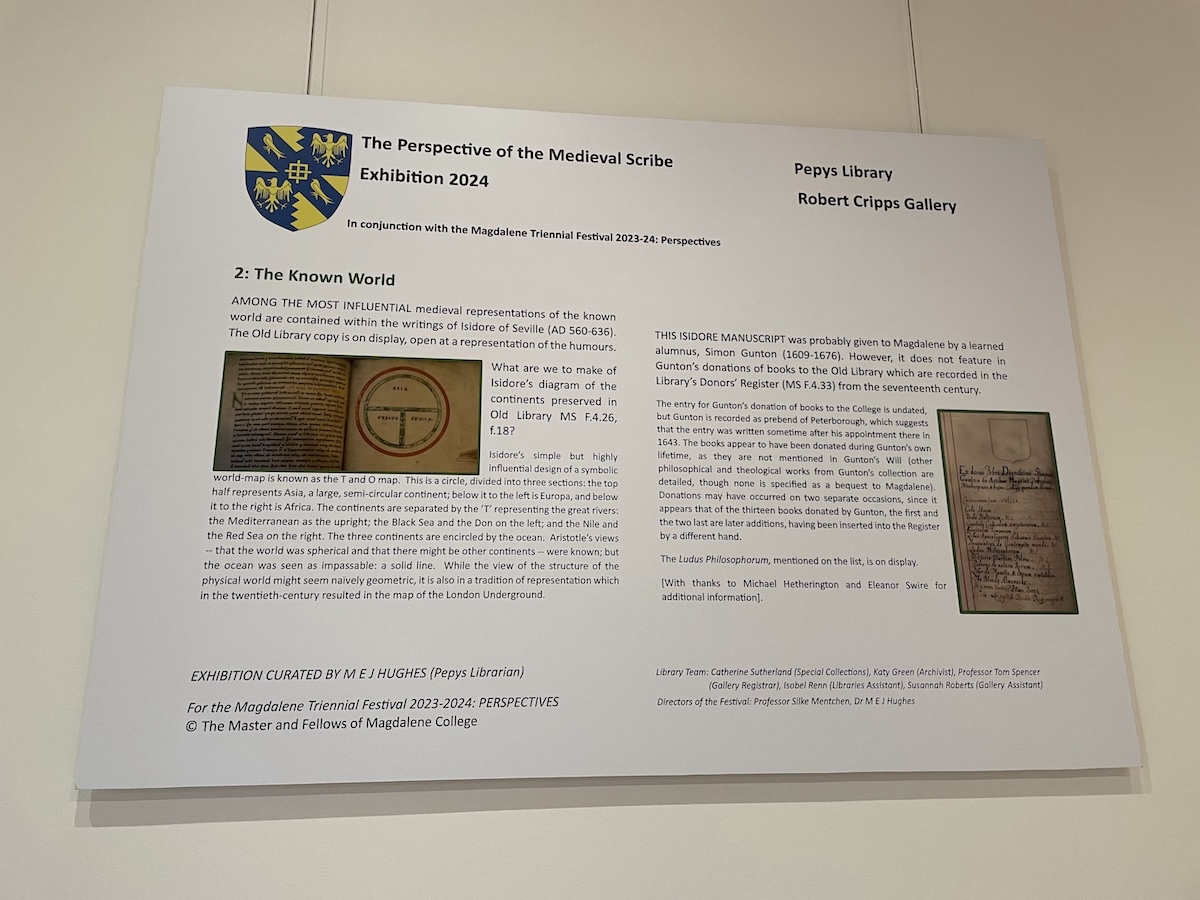

Different perspectives were presented through which a medieval scribe would relate to the world: the layout of the continents in a “T and O” map, religion, nature and the seasons, and the connections between the humoural system, astrology and music. Several texts were displayed in the centre of the room, with interpretative panels discussing the different perspectives on the walls. It could have been made more explicit in parts why certain texts were chosen, or which perspective (or perspectives) they were supposed to relate to.

The strongest sense I was left with, however, was that the exhibit designers felt constrained by the amount of space available to them. Interesting threads of interpretation were started in the display panels, but were typically cut off, before they could actually make a point, by a new thread. Returning to the T and O map, for example, it felt like the writers of the interpretive text wanted to talk about whether the world was conceived of as a disc or a sphere, but were cut off before they actually had a chance to do so.

Similarly, much was made of how different manuscripts ended up in the Magdalene College collection, highlighting figures such as Gilbert Bourne, Barnaby Gooch and Simon Gunton. This could have been an interesting opportunity to discuss why learned men in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were interested in collecting medieval texts, or donating them to their alma maters (especially with one panel and two objects devoted to how many medieval manuscripts have come down to us in fragments, after being taken apart and used in the bindings of printed books), but several panels were devoted to the building of the Old Library instead, which felt out of step with the rest of the exhibit. So - if anyone reading this feels inspired to write a little series of Baelfyr articles… just putting it out there.

While the interpretation left something to be desired, the manuscripts on display were gorgeous and well worth the visit. It is always a treasure to see what different colleges hold in their collections, which are so rarely on display to the public. Some really lovely examples of calligraphy and illumination, including different hands from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries and medieval sacral music. One of the texts, the Peterborough Antiphoner, has been digitised and can be viewed online here in all its glory: https://www.diamm.ac.uk/sources/4873/

[Image description: close-up on a thirteenth century psalter (MS F.4.7), open on a full page illustration of the Adoration of the Magi in shades of red and blue: the Virgin Mary, crowned with the infant Jesus on the right, holds up a red fleur-des-lys. The three kings are gathered presenting gifts, with one kneeling, his crown placed on his knee. /endID]

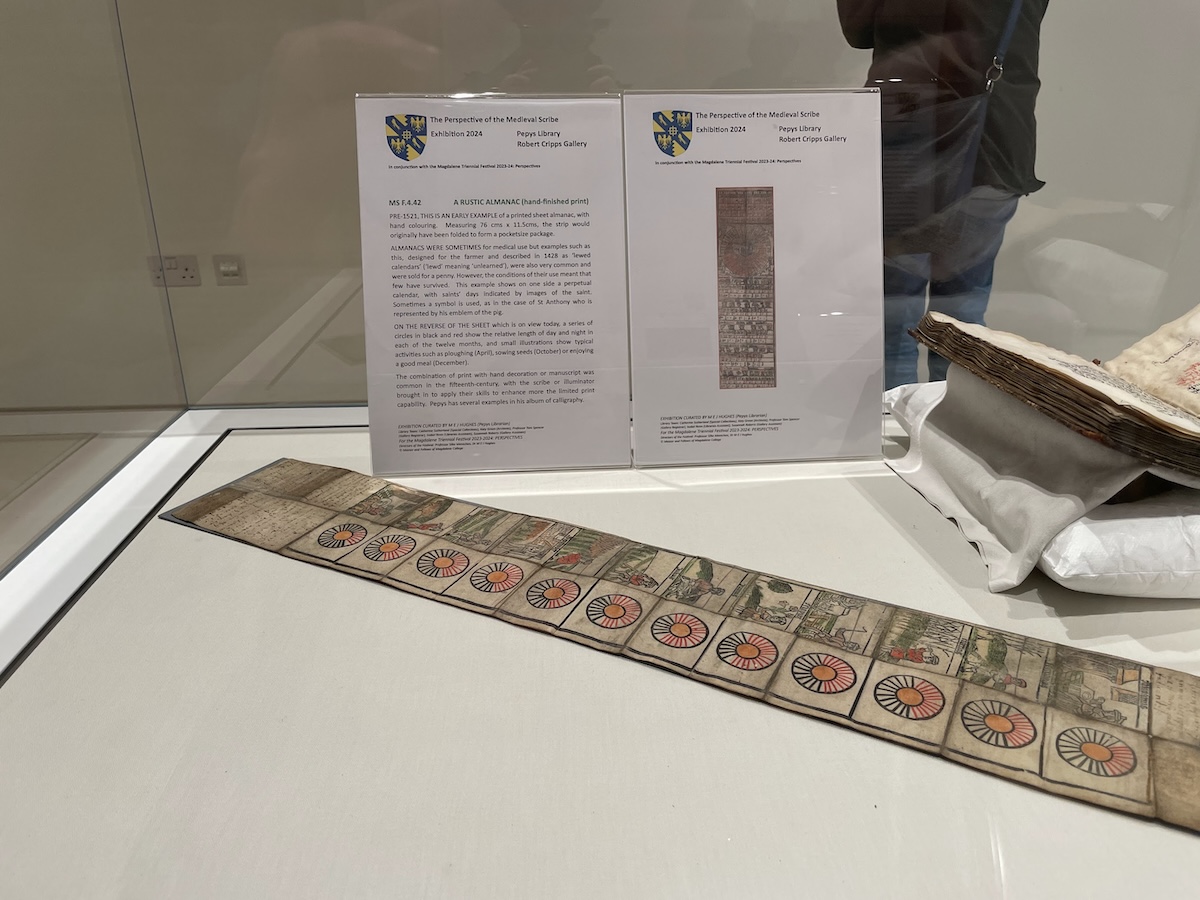

The standout piece for me was this folding almanac, with saints’ days on one side and a representation of the amount of daylight each month on the other. I had never seen anything like it - so much of what has come down to us of medieval documentary culture is of a much higher status. It is so easy to imagine someone pulling this out and unfolding it to check when the next saints’ day would be, or how much daylight they could expect in the coming months.

For a full album of photos, see here: https://photos.app.goo.gl/CyEi3HDxLd5tAHfBA. All should be readable, but unfortunately very few of them are at an ideal angle - the exhibit was not at a friendly height for wheelchair users. This album has brief alt text but not full image descriptions at the moment - if anything in particular interests you, I am happy to write up full image descriptions on request (get in touch with the Chronicler for my email address).

Objects from college collections are often on display annually as part of Open Cambridge, part of the national Heritage Open Days scheme. Watch this space for September 2025 - the Shire of Flintheath will be organising more shire outings!